In 1933 a Hawker Fury aircraft crashed on Thorney Island indirectly creating the birth of RAF Thorney Island.

The Hawker Fury was a 1930s Royal Air Force (RAF) British bi-plane fighter. It was a fast, agile aircraft, and the first interceptor in RAF service quicker than 200 mph (320 km/h) but soon to be replaced by the Hawker Hurricane in 1937 and the Supermarine Spitfire in 1938. The Fury’s of No. 1 Fighter Squadron based at RAF Tangmere were a familiar sight to residents of Emsworth and the surrounding area as they conducted regular training flights over this area. The 25th of September 1933 was just such an occasion. The day dawned bright and clear at the station with a moderate variable or easterly wind and five tenths cloud cover forecast to yield potential showers and a predicted high of 18 degrees Celsius. As the 25-year-old Sergeant William Molesworth Hodge went through his pre-flight checks he may have been thinking that it was just another day at the ‘office’ another routine training flight. As an experienced pilot he was undoubtedly familiar with the Fury which had been introduced into service a few years earlier in 1931. He knew his flight plan well which consisting of a flight along the English Channel towards the Solent and beyond before returning over Portsmouth and Hayling Island before beginning his final approach over Thorney Island. We do not know the exact nature of the difficulties he experienced somewhere over Portsmouth and identifying a flat piece of ground on Thorney Island for a crash landing. The following day The Air Ministry reported in The Times that Mr. A. Nilsson, manager to Mr. C.A. Lundy, the racehorse trainer, who lived at the manor house, stated ‘that the machine hit the ground at a speed of between 180 and 200 mph.’ The head gardener was walking about twenty-five yards away when the crash happened and rushed to the spot. The aeroplane did not catch fire, but the pilot was dead.[1]

No apparent official cause of the crash is recorded although problems associated with the aircrafts Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine had been noted during development and production. These included the engine’s accessory gear trains, coolant jackets, cylinder head cracking, and excessive wear on the camshafts and crankshaft bearings. However, it seems to have been remembered with affection by all who flew it especially those of its acrobatic teams.[2] In the ensuing inquiry by Air Ministry investigators, it was noticed that the island’s topography could lend itself to becoming an RAF station at a time when airfield expansion was becoming urgent with war clouds gathering over Europe.

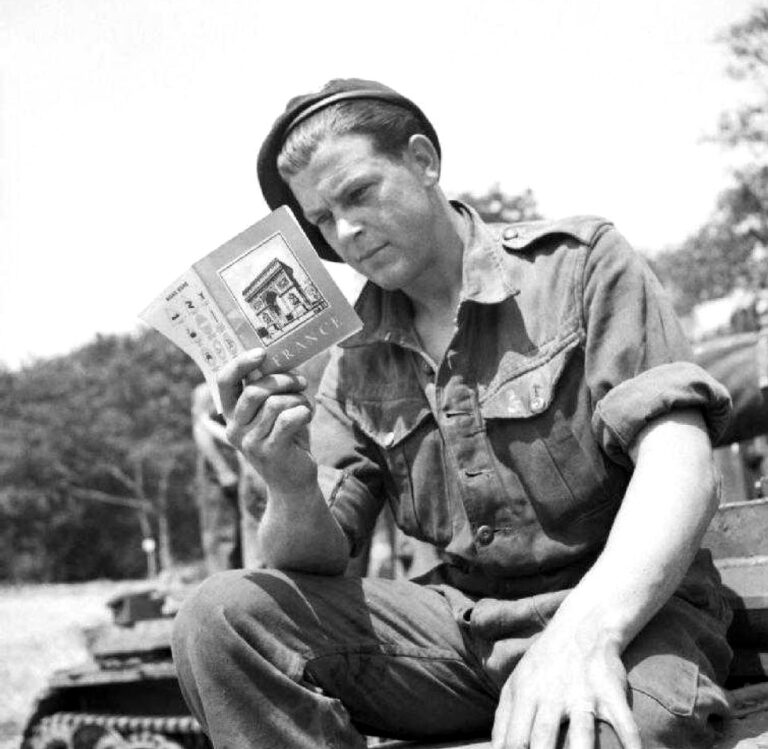

Picture courtesy of David Holton

Just over a year later it was reported that final stages in the negotiations for the purchase of about 1300 acres of land at Thorney Island had been reached for conversion into a Royal Air Force station.[3] By the summer of the following year in 1935 contracts had been placed by the Air Ministry to provide accommodation for five squadrons and a training flight with the cost estimated to be half a million pounds.[4] But what was the Air Ministry going to do about the hundreds of souls resident on the Island?

A Times special correspondent reported that the village was being pulled down with the two to three hundred inhabitants relocated to the mainland. Farms and cottages were being demolished, trees cut down and fields levelled. Where in previous years corn was grown workers were already erecting the framework for two great hangars. When the exodus was completed the Air Ministry would have concluded its plans for developing the island as an RAF station with modern quarters, a new church and a cinema for the men and their families. The education of the children of serving families was under discussion with the West Sussex education authority and it was proposed that a new school was to be built to take the place of the present 78-year-old building.[5] One thousand four hundred acres had been purchased by the Air Ministry for £78, 500 which included compensation for those displaced people. Over half a million pounds was planned for accommodating five squadrons and a training flight. On August 3rd, 1937, it was reported that the aerodrome could be used for the aircraft of personnel visiting on duty in connection with the opening later that month on the 30th but not for widespread use until October 4th. The new station was to be placed under the command of the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief Coastal Command in No. 16 (Reconnaissance) Group.[6]

Interested readers of The Times towards the end of 1937 noted that the opening date for full commission was to slip to March 10th, 1938, include flying boat operation and the move from Donibristle, Fife to Thorney of Nos. 22 and 42 (Torpedo Bomber) Squadrons. This brought the total number of stations formed under the expansion scheme to twenty-seven. [7] In April 1938, the General Reconnaissance School was formed at Thorney upon the closure of its base at RAF Manston, Kent[8] and at the end of the month came an announcement that the King was to visit RAF Thorney Island in May.[9]

The Royal plan was for a tour of inspection of the Fighter, Bomber, Training and Coastal Command arms of the service. These would happen at RAF Northolt, Middlesex; RAF Harwell, Oxfordshire; RAF Upavon, Wiltshire and RAF Thorney Island, West Sussex, respectively. On Monday May 9th, 1938, the Kings private Airspeed ‘Anson’ touched down at ‘the newest and biggest station the RAF can boast – a station which, if the critics are to be believed, is too big and so should be apologized for’ as reported by The Times Aeronautical Correspondent. Those dissenting voices were concerned that its construction for six squadrons was vastly too many eggs to put into one basket. Fifty aircraft were drawn up in an impressive arc, twenty of the twin-engine Avro Ansons as well as Vickers Vildebeest torpedo bombers.[10] One of these aircraft from 22 Squadron RAF Thorney Island whilst engaged in torpedo dropping practice in the Solent a few months after the King’s visit crashed into the sea killing the pilot, Pilot Officer Lesley Morley Barlow.[11] The wheel of misfortune had turned a full circle.

In more recent times a plaque was commissioned probably by a former Garrison Commander when the site was in use by the Royal Artillery.

Phil Magrath, Museum Curator.

[1] No.46559, The Times, Tuesday 26 September 1933, p.11. All The Times references are from The Times Digital Archive go.gale.com/ps/start.do?p=TTDA&u=WSussex

[2] O. Thetford, Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918, Putnam & Company (London, 6th edn., 1976), p.322.

[3] No. 46906, The Times, Thursday 8 November 1934, p.11

[4] No. 47116, The Times, Monday 15 July 1935, p.23

[5] No. 47328, The Times, Friday 20 March 1936, p.11

[6] No. 47720, The Times, Friday 25 June 1937, p.23

[7] No. 47844, The Times, Wednesday 17 November 1937, p.11

[8] No. 47914, The Times, Wednesday 9 February 1938, p.18

[9] No. 47979, The Times, Wednesday 27 April 1938, p.18

[10] No. 47990, The Times, Tuesday 10 May 1938, p.14.

[11] No. 48123, The Times, Wednesday 12 October 1938, p.11